The Losing Battle Against Homelessness in California

Housing and homelessness have been key concerns in California for the past half dozen years. The State has put pressure on cities to increase housing production and has poured money into building permanent supportive housing to house those experiencing homelessness. Unfortunately, this appears to be a losing battle and we must rethink how we are approaching our housing cost and homelessness crisis in the state.

California has been more focused than ever on building Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) to provide both housing and the services people need to get off the streets and stabilize their lives. The vast majority of new funding programs, both at the state and local level, have put the majority of funds into PSH. State programs like RoomKey and HomeKey, and the forthcoming HomeKey+, have diverted most state affordable housing dollars to PSH. Similarly, at the local level, new funding sources like Measure H in LA County and Measure HHH in the City of LA, and new funding organizations like the Orange County Housing Finance Trust, have made additional funding available for PSH.

All of this additional funding has had a measurable impact on the production of homes for lower income households, especially those experiencing homelessness. Between 2018 and 2023, the number of new homes built for lower income households has more than tripled, from just over 5,000 in 2018 to nearly 18,000 in 2023. This is an unmitigated Good Thing ™.

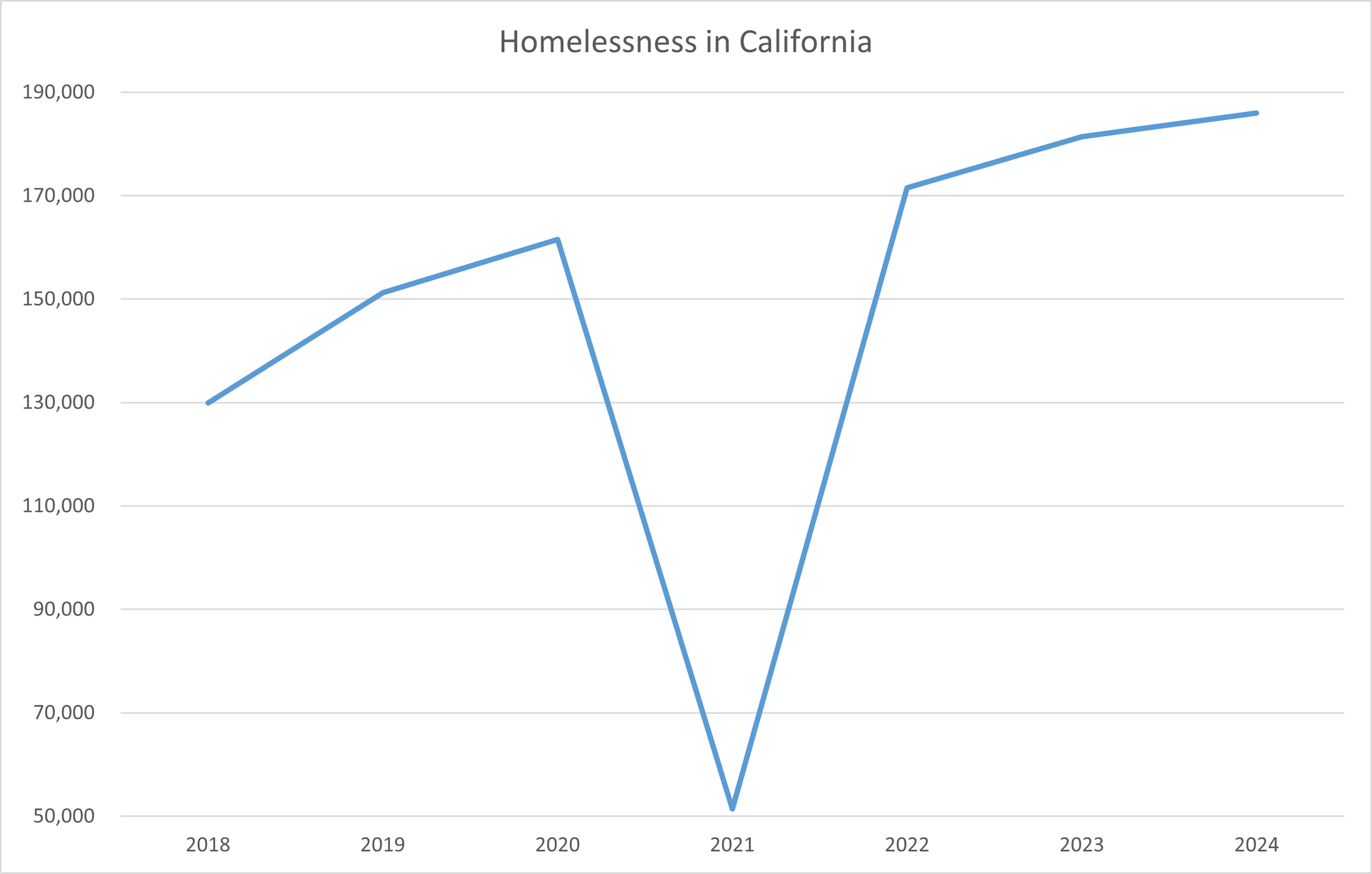

However, over that same time period, the number of Californians living on the street has increased by nearly 50%, from 130 thousand in 2018 to 186 thousand in 2024. (The dip in the graph in 2021 was mostly due to many Continuums of Care, who conduct the annual Point-in-Time Count, simply did not conduct a census of people experiencing homelessness that year due to Covid.)

Each year, California is building less than 10% of the affordable housing it needs. California would need to greatly increase the amount of funds available to build PSH to house its existing homeless population. The average subsidy needed to build an apartment affordable to a very-low income household is about $500,000. To build apartments for all 186 thousand homeless residents of California would cost $93 billion, or twenty times the amount the State has budgeted for housing programs over the next year.

Even worse, despite the increased spending and housing production in recent years, more people are becoming homeless each year than are being placed back into housing. Despite the 7,128 new homes affordable to very-low income households built in 2023, there were about 5,000 more people living on the streets at the start of 2024 than a year earlier, before those homes were built. That means, at a minimum, California needs to nearly double its PSH production to even start to reduce its number of homeless residents.

This illustrates the big problem of how California has been thinking about eliminating homelessness. Mostly, California thinks about providing homes for the people who are homeless today. To end homelessness, California must build 186 thousand PSH apartments and the problem will be solved. But even if the State could do that, next year even more people will be living on the street and in need of housing.

However, homelessness is a flow, not a stock. In other words, people are becoming homeless (inflow) and getting housed (outflow) all the time. California has mostly been focused on increasing the outflow to reduce the stock of people currently homeless. This model isn’t working and is cost prohibitive to make work at all.

Instead of what it has been doing, California needs to focus its efforts to reduce the inflows to homelessness. As has been well documented, homelessness is a housing problem, and California needs to focus on increasing housing stability for households on the edge of homelessness.

The County of Los Angeles is leading this change through Measure A, on the ballot this November. Measure A would replace Measure H, and would go towards funding the Los Angeles County Affordable Housing Solutions Agency (LACAHSA). One of the legally required goals of Measure A is to reduce the number of people falling into homelessness. Approximately 11% of funds raised by Measure A will go towards homelessness prevention and renter support.

There are many programs the State of California could create to reduce inflows into homelessness. Examples of policies to help stabilize housing for households on the brink of homelessness are to provide emergency cash assistance or short-term vouchers to pay for existing housing, enact state-wide rent control to prevent excessive rent hikes, require landlords to notify the State regarding evictions and rent increases, and offer right to counsel for renters.

At the same time, California needs to continue to ramp up production of housing while making it more cost effective. The State can enact programs to increase the availability of construction labor and materials, increase the availability of financing for multi-family construction, and expand the types of homes that can be built.

One of the biggest constraints on housing production is a lack of construction workers and building materials. The number of construction workers across the country is about 2/3rds what it was at its peak in 2006. California could invest some of its education funds to expand construction training program at vocational schools and community colleges. At the same time, the State could encourage building trade unions to expand their apprenticeship and training programs, perhaps by making the requirements for prevailing wages on affordable housing developments contingent upon the availability or training targets of union labor.

Similarly, California could create programs that would increase the supply and lower the cost of building materials for affordable housing developments. The State could bulk buy material and sell it to contractors at cost, or even stand up its own mills and manufacturing plants to crate a dedicated supply of low-cost material for new development in California.

Looking beyond lowering the cost of construction, California could create programs that increase the availability of financing for multi-family construction. One of the biggest boons to single-family home construction was the creation of the Federal Home Loan Bank System, the creation of the standardized 30-year mortgage, and especially the creation of a secondary mortgage market through the establishment of Fannie Mae. California is large enough to duplicate this effort for multi-family project debt by creating standardized underwriting guidelines for multi-family debt and then purchase debt that meets those guidelines to create mortgage-backed securities to sell on the secondary market. This would provide for significantly more financing available for multi-family construction while also providing an additional profit center for the State.

Finally, California needs to modernize and update its building codes to allow for a greater range of building types and improved urban form. Today, it is difficult to build anything other than large apartment complexes, 5-over-1 mixed-use buildings, or single-family homes. More than anything, this is due to the building code, not zoning or any other governmental regulation.

California’s are modeled off of the International Code Council’s International Building Code. This code effectively prohibits most forms of missing middle housing, either directly or indirectly by making buildings cost prohibitive. California is already studying whether to enact single-stair reform to enable point access blocks. It needs to go further and do a full analysis of the cumulative cost benefit of each code provision, and how they interact with other requirements such as from the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Overall, California has been making admirable strides towards tackling homelessness in the state. Unfortunately, its efforts are too little and not focused in the right areas to improve the homelessness crisis. California needs to rethink how its addressing homelessness if it wishes to truly end it.